"Never change a running system." It's a philosophy I've always adhered to. Excitement in tech usually equates to instability, something I'm not particularly fond of. It might sound strange coming from a startup CTO, but let me explain in this article what I mean.

If you've found your way to this article, it's likely because the idea of a Unified Namespace (UNS) intrigues you. You're considering how it could fit into your company's framework, potentially streamlining processes and enhancing data handling. But you're faced with a hurdle - how do you integrate the UNS with your established IT landscape, systems such as AWS, Azure, Data Lakes, and Data Warehouses?

Unified Namespace is a powerful tool, a form of event-driven architecture where all data is published irrespective of immediate demand. However, its practical integration with traditional IT frameworks often leaves many scratching their heads.

In this article, we'll provide a roadmap to successfully incorporate UNS into your enterprise architecture. We'll navigate the distinct requirements of frontline workers and business analysts in Chapter 1, exploring the roles of OLTP and OLAP databases. Chapter 2 will focus on managing large volumes of real-time and historical data through the lens of the Lambda Architecture. In the final chapter, we'll tie everything together, offering an actionable approach to integrate these elements seamlessly into your enterprise landscape.

Along this journey, if you find value in these insights, I'd encourage you to connect with us. Whether it's through LinkedIn, Discord, or our newsletter, we're always keen to engage with like-minded professionals looking to make the most of technologies like the Unified Namespace.

Dashboards for Frontline Workers and Business Analysts - Bridging OLTP and OLAP

Navigating the diverse data needs of frontline workers and business analysts requires the tactful orchestration of two distinct types of databases - OLTP (Online Transaction Processing) and OLAP (Online Analytical Processing). On the one hand, frontline workers need immediate access to up-to-date data to ensure smooth operation of the factory. On the other hand, business analysts require both breadth and depth of data, spanning extended periods, to identify potential improvement opportunities. This is where OLTP systems come in for frontline workers, and OLAP systems for business analysts.

OLTP Systems are built for routine transactions, analogous to your daily online banking or shopping. Mostly used by end-users or customers through web applications, these systems strive to keep data current at all times. They handle datasets ranging from gigabytes to terabytes in size, with a majority of SQL databases qualifying as OLTP databases.

In contrast, OLAP Systems or Data Warehouses are tailored for more complex tasks like data mining, business intelligence, and intricate analytical calculations. These systems are capable of handling immense volumes of data, often used for bulk data import (ETL) or data streams. Primarily leveraged by internal analysts for decision support, OLAP systems hold larger datasets, from terabytes to petabytes. Some examples include Data Warehouses, Data Lakes, Azure Synapse Analytics, AWS Redshift, and others.

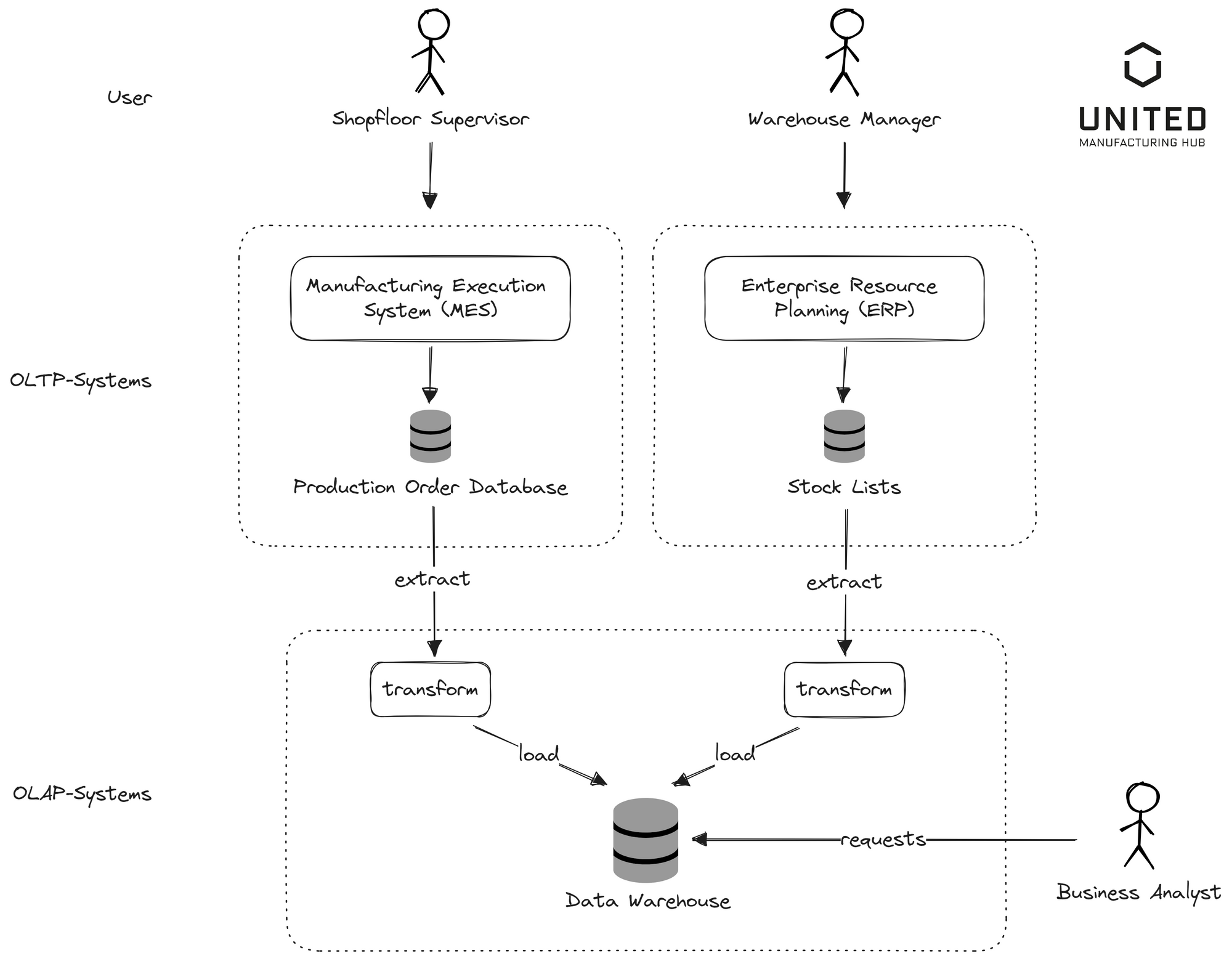

To harmonize the functions of these two systems, an ETL (Extract, Transform, Load) process is typically used. Traditionally, this is a batch process, often executed overnight. It extracts data from the OLTP system, transforms it to be analytically useful, and loads it into the OLAP system.

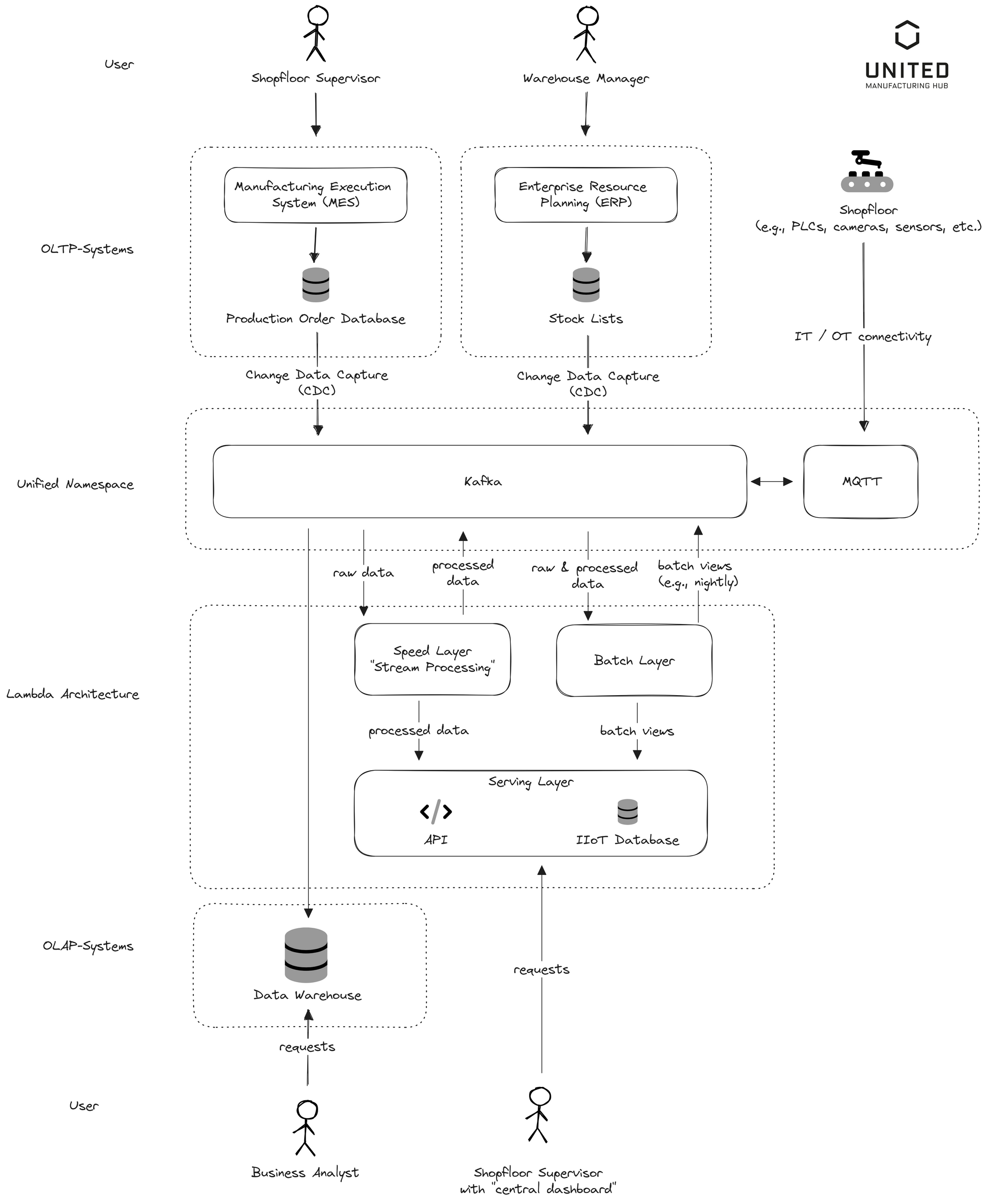

As the image above illustrates, in a manufacturing process, data from a Production Order Database (from a MES) and a Stock Lists Database (from an ERP) feed into an ETL process. This processed data is then stored in a Data Warehouse where business analysts can analyze the data. A shop floor supervisor inputs data into the MES, while the Warehouse Manager feeds data into the ERP system.

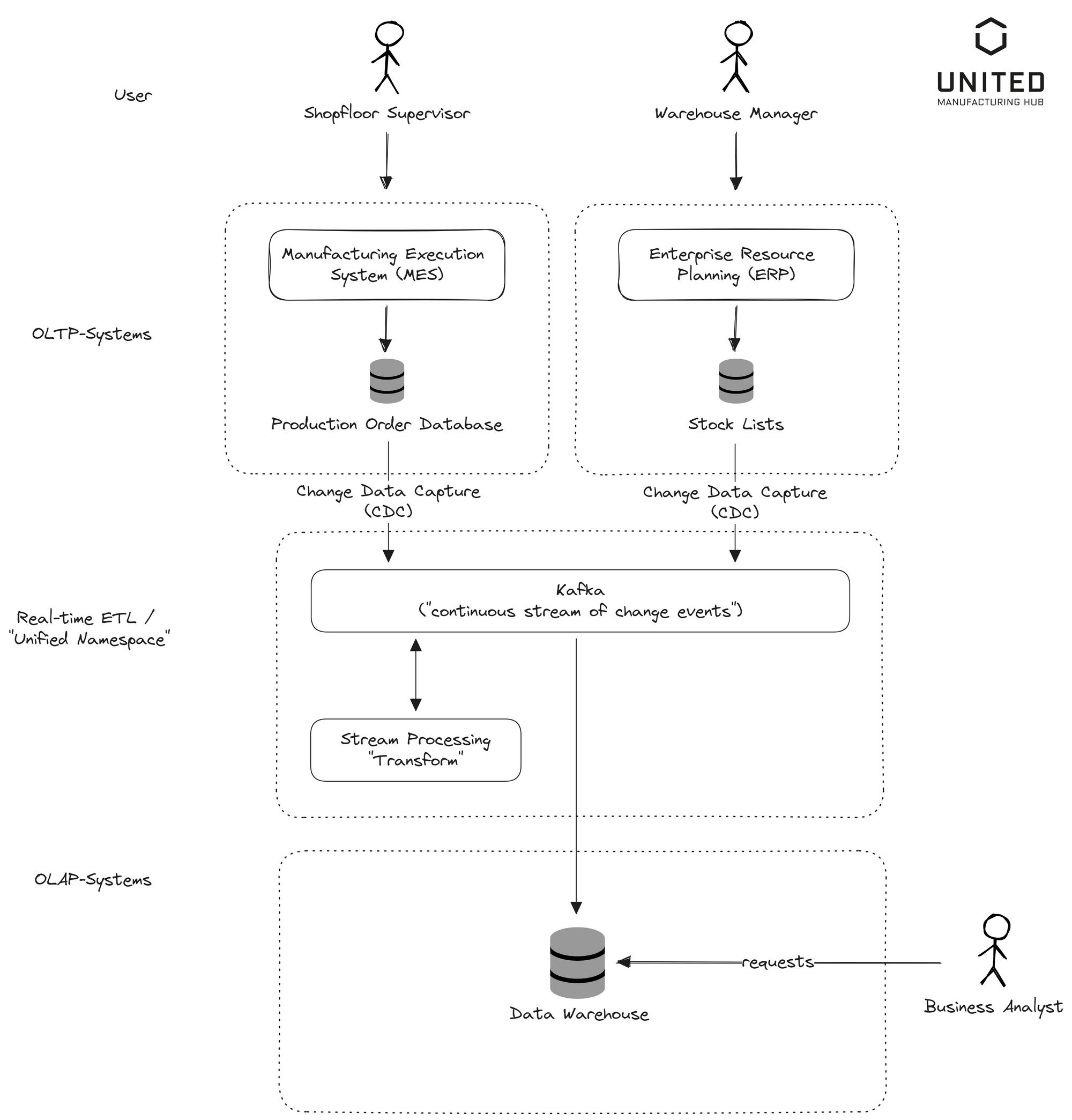

But in the modern data landscape, the demand for real-time insights is transforming the traditional ETL processes. The recent trend veers towards real-time or near real-time ETL processes (see image below). In this approach, data is streamed from the OLTP to the OLAP system as events occur, a technique known as Change Data Capture (CDC), facilitated by tools like Debezium and Kafka Connect. The data undergoes transformation and loading into the OLAP system almost instantly, in a process called "streaming ETL" or "real-time ETL". This real-time data stream is highly beneficial for real-time analytics, fraud detection, and system monitoring, with platforms like Apache Kafka being commonly employed.

If you're familiar with the Unified Namespace (MQTT + Kafka), you might find similarities between it and the real-time ETL process. This is because the Unified Namespace effectively bridges the gap between the OLTP and OLAP systems. It links all the relational databases on the shop floor with data from other devices, such as PLCs, offering a continuous stream of change events from the Operational Technology (OT) world. This streaming data signifies the 'Extract' step in the ETL process. Moreover, the data within the Unified Namespace undergoes 'contextualization' - a parallel to the 'Transform' step in ETL, which adjusts tag names, performs minor calculations, and prepares data for analytical use.

While the Unified Namespace, combining MQTT and Kafka, shows resemblances to a real-time ETL process, it's important to clarify its unique characteristics. The 'Unified Namespace' is encapsulated within quotes as it functions similarly to an ETL process only when Kafka is incorporated. Standard message brokers like MQTT lack an internal storage feature, vital for data processing beyond delivery. This means, without Kafka, we miss out on features such as backpressure handling and the ability to replay historical data. To understand this in more depth and understand why you need MQTT and (!) Kafka, refer to our article "Tools & Techniques for Scalable Data Processing in Industrial IoT".

Now that we've traversed the landscape of OLTP and OLAP databases and seen the shift to real-time ETL processes, we're equipped to explore further. In the next chapter, we will turn our attention to the Lambda Architecture.

Processing Large Amounts of Data - Real-Time and Historical: The Lambda & Kappa Architectures

Introduced between the early and mid-2010s, the Lambda Architecture was devised to blend emerging real-time ETL and streaming analytics such as those within the Kafka ecosystem, with conventional batch processing tools, for instance, MapReduce.

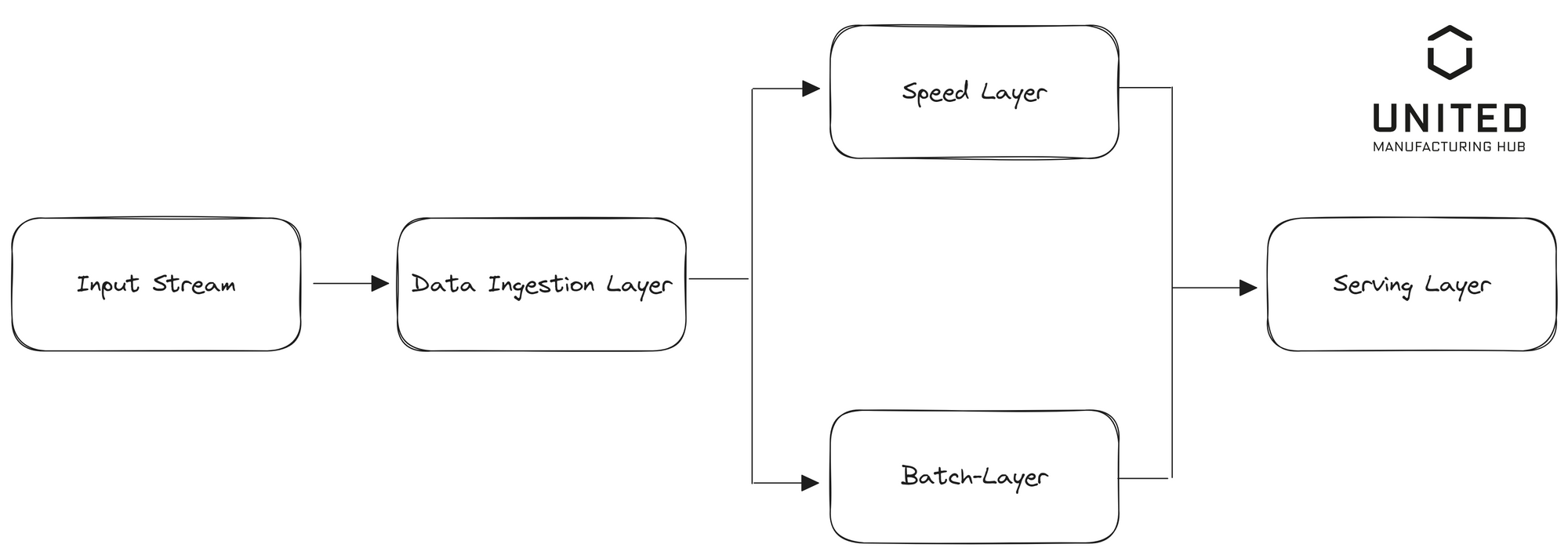

This architecture is built upon three core layers: a batch layer, a speed layer (also known as the hot path), and a serving layer. The batch layer, often seen as the computational engine, provides extensive and precise views of batch data. On the other hand, the speed layer caters to the immediate demands of real-time data, while the serving layer allows for querying the combined output of the batch and speed layers.

The architecture draws its name from the Greek letter "λ" (lambda), with the symbol's intersecting lines depicting the dual paths of the speed and batch layers. Under this architectural blueprint, the Unified Namespace serves as the speed layer. To give a real-world example, let's examine a Predictive Maintenance scenario in a Lambda Architecture setting:

- Speed Layer (Unified Namespace): This layer handles real-time data from machinery. Any anomalies from the standard patterns, as flagged by the model trained on the batch layer, would trigger immediate alerts for rectification. The output from the speed layer provides a real-time view of machine health.

- Batch Layer: This layer manages and processes historical data from machinery, such as temperature readings, vibrations, hours of operation, and error logs. At scheduled intervals, machine learning models are trained on this data, allowing them to predict potential failures or maintenance needs outputting AI models. The outcome is also a batch view that presents predictions based on patterns discovered in the historical data.

- Serving Layer: This layer marries the historical predictions from the batch layer with the real-time health data from the speed layer (Unified Namespace). It enables quick access to predictive maintenance data, facilitating both historical trend analysis and real-time machinery health monitoring. This layer often manifests as a "dashboard" that displays both the current equipment status and the historical data for contextual understanding.

Using the Lambda Architecture design pattern with the Unified Namespace as the speed layer allows shop floor supervisors to access all pertinent information in one centralized location. However, it's essential to consider whether this architecture might be an overcomplication for some use-cases.

Common tools used in the Batch Layer, such as MapReduce, are typically employed for processing terabytes of data – a scenario not often encountered in manufacturing. Specifically, MapReduce was developed by Google in 2004 to build indexes for its search engine. The only frequent use-case requiring such extensive data processing involves machine learning and model building. For instance, storing all product images and retraining the machine learning model on a weekly basis.

One of the drawbacks of the Lambda Architecture is the need to maintain identical logic across multiple systems (speed and batch), and the challenge of harmonizing real-time and batch analyses in the serving layer.

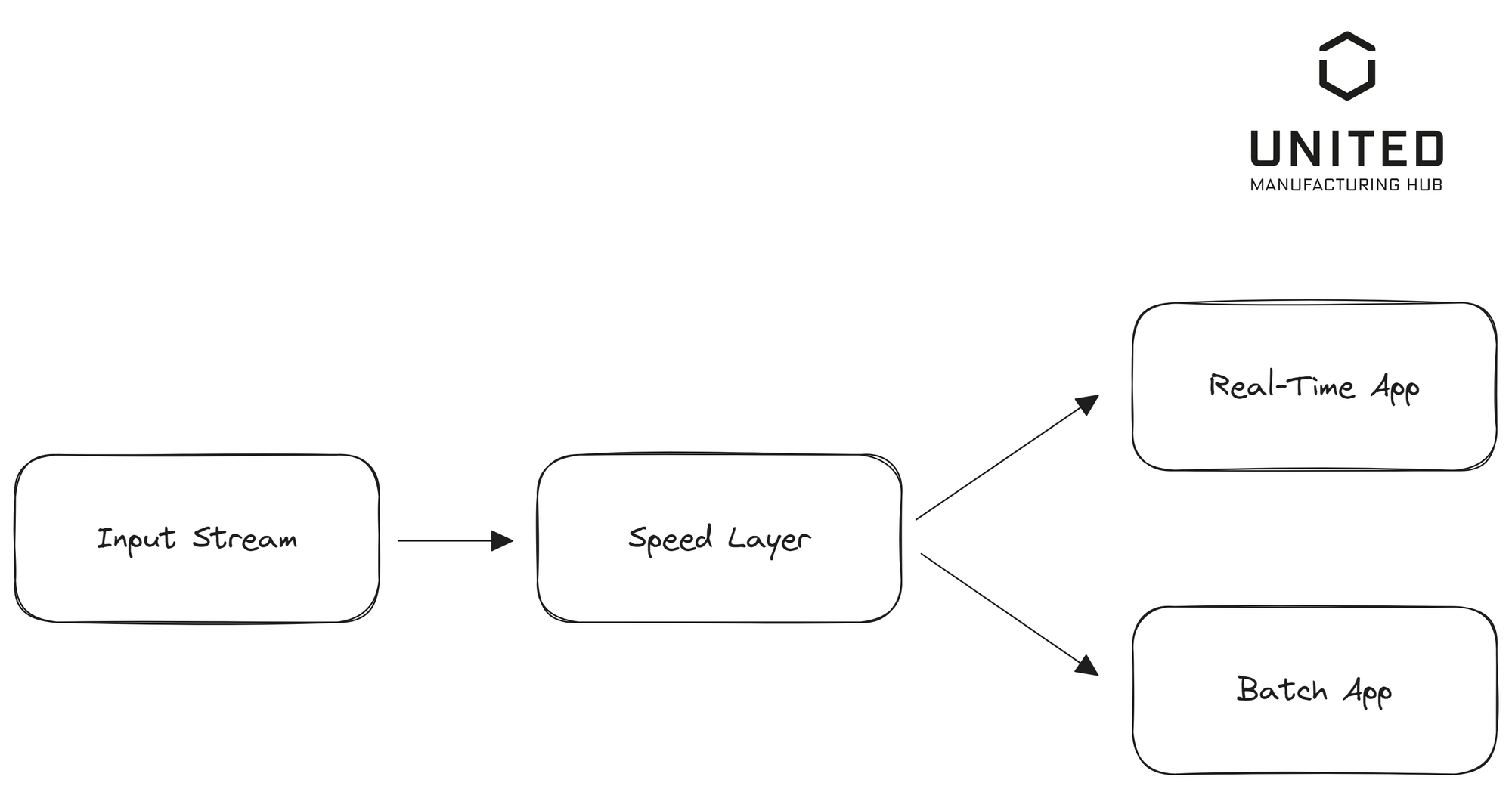

Alternatives, like the Kappa Architecture, have been proposed. Jay Kreps, CEO of Confluent and the driving force behind Apache Kafka, introduced the Kappa Architecture in 2014. Notably, this architecture omits the batch layer, which makes the system much more easier to maintain. If you want to find more about it, where its used, and what the differences are compared to Lambda architecture, check out Kai Waehner's blog post about it called "Kappa Architecture is Mainstream Replacing Lambda".

As we move to the next chapter, we'll address a common question: "This sounds great, but how can I apply this in my manufacturing setup?" We'll explore how all these components fit together in a practical, industry-specific context, further unlocking the power and potential of the Lambda Architecture.

One Architecture to rule them all,

One Architecture to find them, One Architecture to bring them all, and in the enlightenment bind them; in the land of manufacturing where IT / OT components lie.

As a reminder of our journey so far, we've examined the role of OLTP databases for frontline workers, OLAP databases for business analysts, and Lambda Architecture to handle real-time and historical data. Now, we'll explore how to integrate these components effectively.

Bringing OLTP, OLAP and Lambda together into a UNS-based architecture

Let's visualize and understand how these elements collaborate in a single, harmonious system (see image below).

Relational databases such as the MES or ERP on the shop floor are linked to Kafka via Change Data Capture (CDC), as discussed in Chapter 1. This establishes a real-time ETL connection from the OLTP databases to the Unified Namespace (UNS), further extending it to the OLAP databases. In the manufacturing context, we incorporate additional data sources from the shop floor - IoT devices like PLCs, cameras, sensors, and more - either from the automation pyramid or entirely new data sources. These devices are typically connected to an MQTT broker, which then bridges to Kafka. MQTT efficiently handles numerous unreliable connections, but struggles with large data volumes. Kafka, on the other hand, excels in processing large amounts of data but struggles with maintaining numerous unreliable connections. In manufacturing, these strengths are typically combined to optimal effect. The connection from the shop floor to the UNS, also known as IT/OT connectivity, often involves other protocols like OPC-UA besides MQTT.

A Lambda architecture is built atop Kafka. The speed layer comprises one or more "stream processors" that take raw data from Kafka, "contextualize" or "transform" it (e.g., changing tag names, providing background information like unit, etc.), and then send processed data back to Kafka and into the serving layer. The batch layer is connected to Kafka and the serving layer as well and takes raw data from Kafka, and transforms it through regular batch jobs, such as training an AI model or calculating the Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE), returning the results to Kafka and the serving layer. If batch jobs are not required, then one can leave out the batch layer and opt-in for a more "Kappa-styled" architecture.

The serving layer offers access to all real-time (speed layer) and historical data (batch layer + IIoT database) via an API such as REST or GraphQL. The shop floor supervisor can access it using a tool like Grafana for "centralized shop floor dashboards." As all data, raw, real-time processed, and batch-processed, is available in Kafka, the business analyst only needs to subscribe to it and transfer it into his Data Warehouse or Data Lake to run analytics, create reports in BI tools, or develop new AI models.

Certainly, you might think: This is an impressive architecture, but merely showcasing dashboards doesn't enhance production. You'd be correct. All the insights we've generated are readily accessible in the Unified Namespace. This means it's now incredibly straightforward to subscribe to any data type—be it raw data like PLC tags, derived real-time data such as current equipment status (in the diagram called "processed data"), or batch data like the OEE—and subsequently trigger an action on the shop floor.

These actions could range from turning a traffic light red to automatically discarding a defective product in instances of AI-assisted quality control and image classification. In the jargon of data architecture, this is known as "Reverse-ETL."

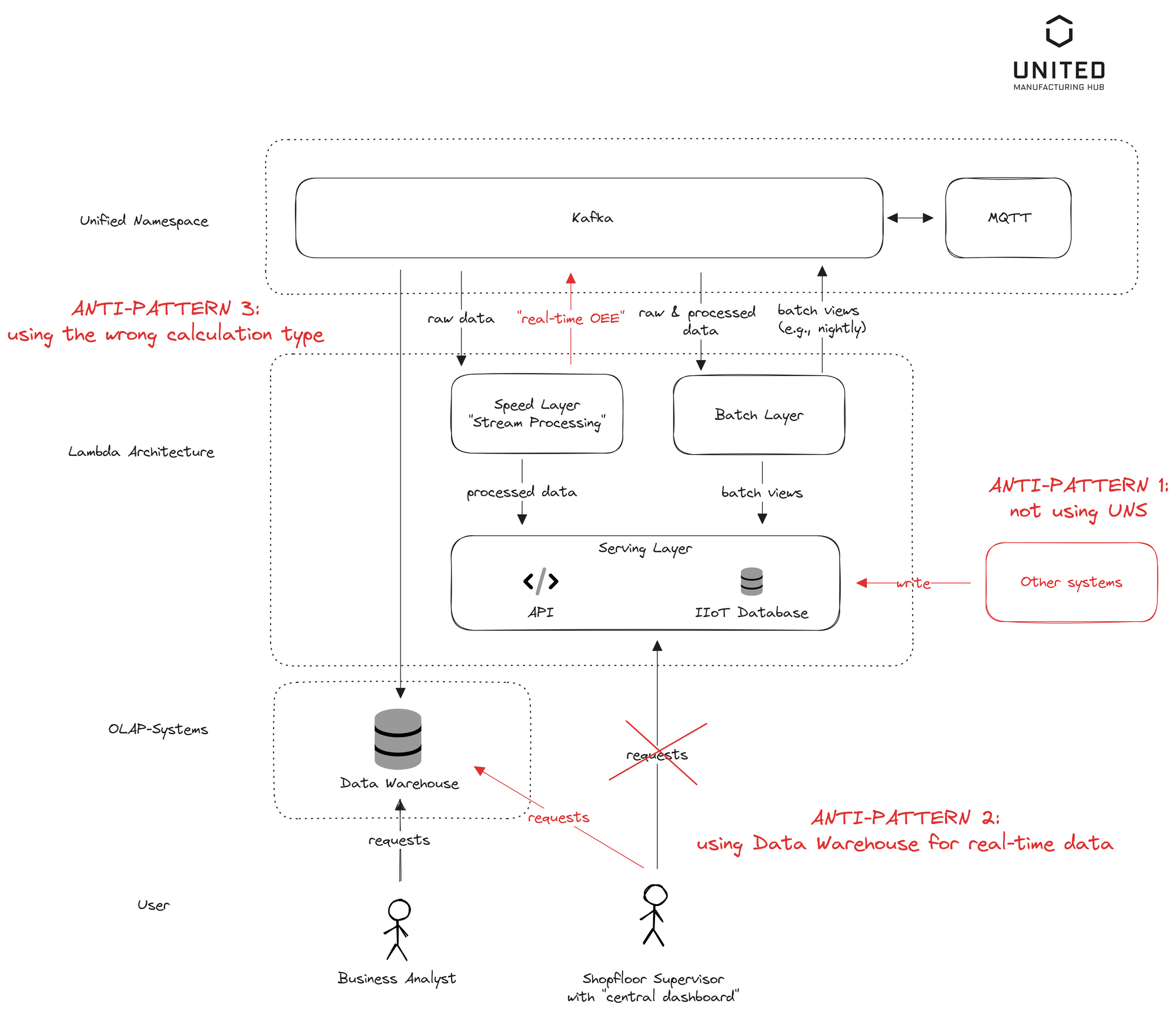

Anti-patterns

Let's discuss some common pitfalls encountered when implementing such an architecture and potential solutions to these issues (see also below image).

Anti-Pattern 1: Storing data from the Unified Namespace in an OLTP database, and then appending additional system information creates a gap between OLTP and OLAP systems. One solution is to write into the OLTP database exclusively via the UNS. One company we know added data directly in via SQL into the IIoT database. It worked perfectly fine, but then they lost themselves in spaghetti diagrams when talking about how one can send this information to other systems as well.

Anti-Pattern 2: Using the Data Warehouse for frontline workers. Some analyses demand too much time to be useful for "real-time dashboard" and need to be cached to improve performance. One factory we know sent all their data into an Azure based Data Lake and retrieved it via PowerBI. It was great for reporting, but the time delays were to much for working with it on the shopfloor.

Anti-Pattern 3: Using the inappropriate calculation type (stream or batch) for the specific use-case. We have synchronous (API accessing the database with caching) and batch calculations (performing it nightly). Then there's stream processing (e.g., not recommended for OEE). One factory we know tried to do everything using batch processing, which was fine for reporting, but really not helpful to identify whether a product was good/bad during the production cycle.

How we do it at the United Manufacturing Hub

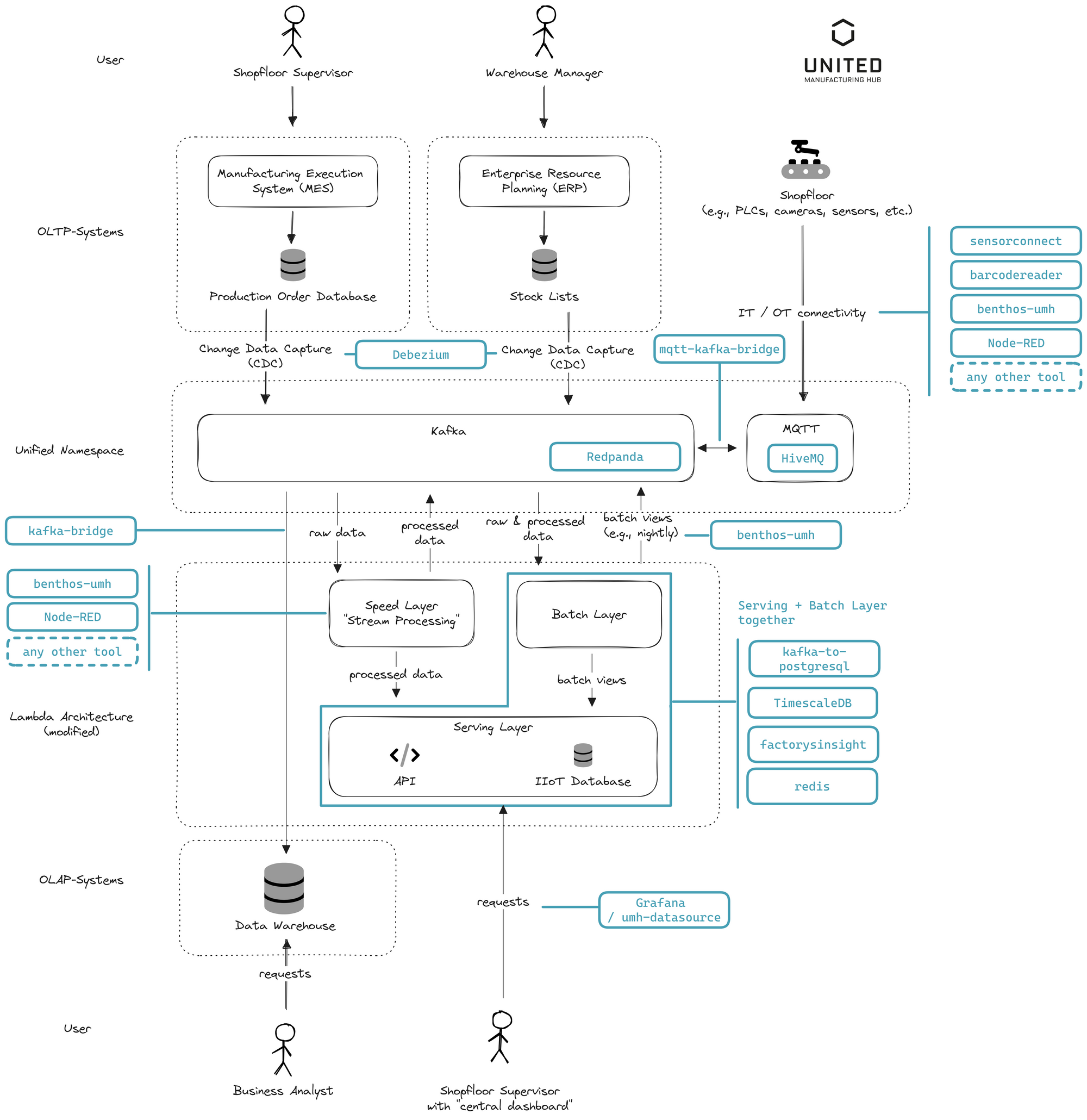

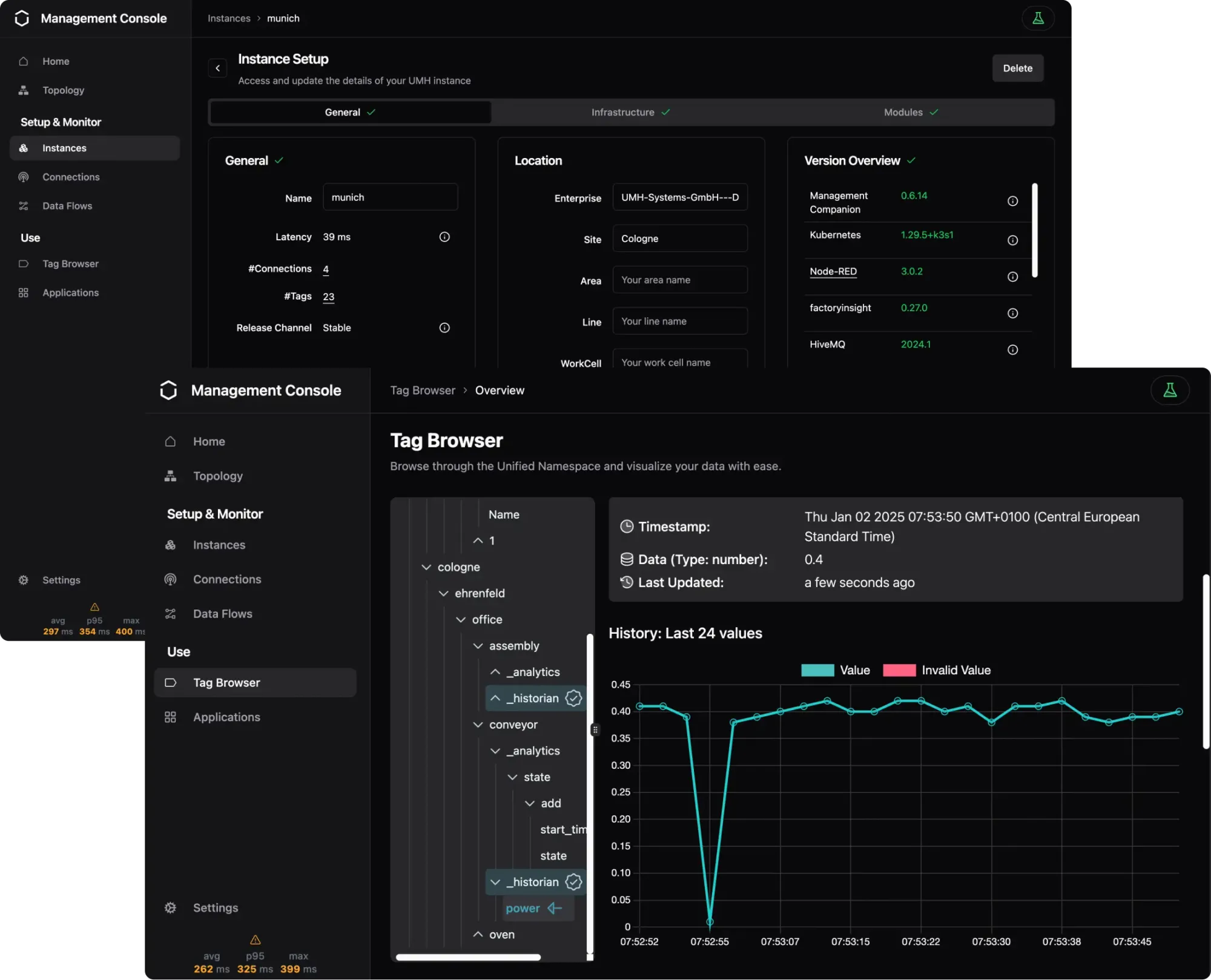

Let's take a look at how United Manufacturing Hub (UMH) has seamlessly integrated all these components and provide a brief explanation.

In the United Manufacturing Hub, we offer most (though not all) of these components by default in a single package. For more information, check out this link. With a tool like Debezium, one can connect existing relational databases on the shop floor. Common databases like PostgreSQL or Microsoft SQL are far easier to connect than rare databases such as SQL Anywhere.

Devices on the shop floor can be connected either via our microservices sensorconnect, barcodereader, or the open-source benthos-umh (for OPC-UA), or via standard connectivity tools like Node-RED or Kepware. Everything lands up then in HiveMQ and Redpanda (Kafka-compatible software). The real-time data can then be processed in Node-RED, benthos-umh (our recommendation for scalable data processing, although it may not be intuitive for OT engineers), or any other tool available on the market (Apache NiFi, Crosser, HighByte, etc.).

Redpanda is our choice over traditional Apache Kafka as it fits better the typical UMH user, who often deploys UMH at the edge. Here, the advantages of simplicity and resource efficiency take precedence over scalability. Although Redpanda is Kafka-compatible, it's important to note that its relying on the Kafka protocol and does not offer the full set of Kafka's features. For instance, offerings like tiered storage aren't available with Redpanda. However, we find its lightweight design, based on C++, very suitable for the needs of the typical UMH user. Larger enterprises often opt for traditional Kafka solutions from companies like Confluentfor their on-premise or cloud deployments, where different priorities (Maturity, Scalability, proven SLAs, etc.) over simplicity and resource efficiency may apply.

By default, data is automatically stored from the Unified Namespace in TimescaleDB, where our custom-built API factoryinsight serves as the serving layer. From there, tools like benthos or Node-RED can regularly query data (such as the OEE) and push it back to Kafka.

In our system at UMH, we've elected to diverge from the conventional Lambda Architecture, adopting instead a Kappa-style design. Typical computations carried out on the shop floor, like OEE, may be complex and take a few seconds, but they're not so intricate as to demand hours. Thus, a full-scale batch layer might be excessive, particularly when weighed against the trade-off of increased system maintenance.

Instead, we adopt a more streamlined approach. All data is stored in the IIoT database, and OEE calculations are performed only as needed, based on this existing data. Intermediate results, such as hourly OEE, are cached in Redis for efficiency.

To recap, the Lambda Architecture would typically employ a Kafka consumer or microservice to gather all data from Kafka, storing intermediary OEE results (like an hourly OEE) in a database. The serving layer would then consolidate these OEE results into a larger timeframe, such as a weekly OEE, and retrieve the most recent data from the speed layer to ensure the OEE is up to date. While this might seem excessive for OEE calculations, for other applications like AI model building, such an approach might be justified. Consequently, we've included it in this article to present a comprehensive architecture.

In the UMH, we do not provide a solution for the data warehouse, but our experience suggests that most business analysts are quite satisfied with a continuous stream of all changes in Kafka, simplifying the analytics process.

Summary

Reflecting on my initial mantra, "Never change a running system," you can now appreciate its depth. It's not about being resistant to innovation or change, but leveraging existing, well-established tools and techniques to address our challenges. In this context, it translates to understanding how we can harness the power of familiar systems to integrate the Unified Namespace into our enterprise landscape successfully. We don't need to reinvent the wheel - just learn to use it more efficiently.

Throughout this journey, we began by understanding the distinct data requirements of frontline workers and business analysts, highlighting the roles of OLTP and OLAP databases. Moving forward, we dived into the nuances of managing large volumes of real-time and historical data through the lens of the Lambda Architecture. Finally, we brought these elements together, offering a practical approach to seamlessly integrate the Unified Namespace into your enterprise landscape.

Our aim is to foster understanding and inspire action. Therefore, let me reiterate the crux of our exploration: integrating the Unified Namespace into your enterprise architecture enables real-time and historical data management, effectively bridging the gap between your operational technology (OT) systems and your IT landscape.

Acknowledgement

Thank you to the following persons for providing me with feedback and guiding me through writing this article:

- Pascal Brokmeier

- Kai Waehner

- Akos Csiszar

- Daniel Helmersson

- ChatGPT (for helping me write proper sentences)

And of course our customers and community members for their feedback.

TL;DR powered by ChatGPT

The article explains how to integrate a Unified Namespace (UNS) into enterprise architecture, specifically focusing on frontline workers and business analysts' diverse data needs. It highlights the role of OLTP and OLAP databases, the Lambda Architecture for handling real-time and historical data, and the concept of real-time ETL processes. The author suggests utilizing the UNS as the speed layer within the Lambda Architecture, bridging the gap between OLTP and OLAP systems. The piece concludes with a practical guide on harmoniously merging these components in a manufacturing setup, presenting the United Manufacturing Hub as a real-world example.

IT / OT Integration Platform for Industrial DataOps

Connect all your machines and systems with our Open-Source IT/OT Integration Platform to make all shop-floor data accessible at a single point.